BOOM!

Well, 2022 is starting off with a Bang, that’s for sure. By now, the reports and images about the cataclysmic explosion of the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano in Tonga have spread around the world. Tsunamis have devastated the coastal regions of nearby islands, with the island of Atata near Tonga having apparently been completely flooded. The explosion was heard as far away as New Zealand and even Alaska, while the ash cloud produced by the eruption reached well into the stratosphere, topping out at 20 kilometers and being clearly visible on satellite images and recordings, even at the lowest magnification settings. Radar imagery taken by Earth observation satellites meanwhile shows that the volcanic cone built up by the mostly underwater volcano in recent years and that had linked the islands of Hunga Tonga and Hunga Ha’apai has simply ceased to be. Not a trace of it remains above water, while the two islands themselves have been greatly reduced in size.

|

| This sequence, captured by NOAA's GOES West satellites become synonymous with the Tonga eruption. |

|

| This sequence was recorded by Himawari-8, one of a series of weather satellites operated by the Japanese Meteorological Agency. The volcano is pretty much right in the centre. |

|

| Another image taken by Himawari-8, showing the growing volcanic ash cloud. |

🔴 At 17:08 UTC yesterday, #Copernicus #Sentinel1 🇪🇺🛰️captured the 1⃣st image of #HungaTonga 🌋after the destructive eruption

— Copernicus EU (@CopernicusEU) January 16, 2022

The volcanic island is almost completely wiped out

⬇️ Comparison before (3 Jan.) / after (image of 15 Jan., ~12 hours after the eruption)#Tonga pic.twitter.com/KA98HTQCBz

The actual amount of damage on Tonga itself, as well as on many of the other nearby islands is unknown. Communications with the region are sketchy as undersea telecommunication cables were damaged by the eruption. Both Australia and New Zealand, who are effectively the regional hegemons in that part of the world, are readying air force and navy assets to assess the damage and provide support. The amount of ash fall in the area is likely to be immense as the ash cloud has reached a size that would cover most of France. In a weird twist of fate, the two fatalities and three injuries caused by this massive eruption so far weren’t registered in Tonga but in the Americas. In the city of Lambayeque in Peru, two women were killed when the truck they were in was hit by a two metre tsunami, while in two different incidents in California, people suffered injuries while being washed out to sea by the tsunami.

Then, there was the explosion. The videos from Tonga that made it out before the undersea cables were taken out are awe-inspiring and indicate that parts of the volcanic cone may have been ejected at supersonic speeds. The blast shattered windows in the region and was clearly heard in New Zealand and even in Fairbanks, Alaska, almost ten thousand kilometres away from the volcano. But even beyond the audible, the blast wave traversed the entire planet, including Ireland. At around 18:44 on the evening of January 15th, weather stations around Cork Harbour detected a sudden increase and then decrease in air pressure as the shock wave raced over Ireland. This was followed by the second shock wave at 01:20 on Sunday morning.

It looks like the pressure wave from the volcanic explosion in Tonga in the Pacific was picked up in Cobh by a weather station at 18:44 UTC @CorkHarbourWX @EoinBearla @MetEireann pic.twitter.com/pzANnotE2Y

— John Desmond (@JohnDesmond) January 15, 2022

It had never occurred to me that an event literally on the other side of the planet would have a measurable impact on Ireland but as I read through the media reports and my Twitter feed on Sunday morning, I decided to check the recordings on my Netatmo weather station, just in case. And much to my surprise, there it was!

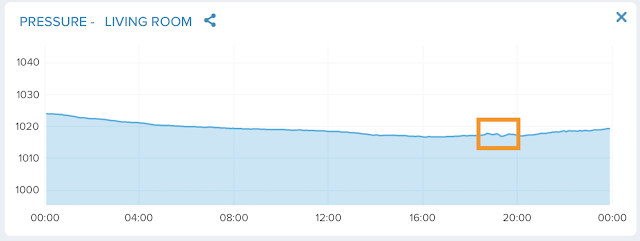

Now, the scaling of my weather station is not the best, neither is the resolution, as it only record measurements in ten minute intervals, but the pattern was clearly there: A disturbance starting at around 18:44, two peaks separated by a trough, followed by a stronger dip in pressure before air pressure returned to its normal values. Then, a similar pattern showed up at 01:20 with a gentle peak, followed by two dips, the second of which was the deeper one, and a period of somewhat chaotic fluctuations before the pressure returned to its usual values. Now neither the measurements taken in Cobh nor mine are anything major. The outside stations show a 1-1.2 hPa shock wave, while my own indoor weather station showed a 1 hPa shockwave. Yes, my station actually measures pressure in millibar but the conversion from hPa to mbar is 1:1, hence the comparison.

|

| This is a visualisation of the raw data exported from the station to make the pressure waves more distinct. The disturbances caused by the two shock waves, marked in orange, are clearly visible here. |

However, the very fact that the Tonga eruption was powerful enough to be registered by an indoor weather station on the other side of the planet speaks volumes about the forces at play here. While the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai eruption is currently tentatively classed as a 5 on the Volcanic Explosivity Index, similar to the 1980 eruption of Mount Saint Helens, this classification seems doubtful to me, as the sheer ferocity of the blast wave dwarves even the cataclysmic eruption of Krakatoa in 1883, which had been heard 4890 kilometres away. It shows another fact equally clearly, namely the interconnectedness of the world, something that in an age of increasingly erratic weather patterns, influenced by anthropogenic climate change, we would do well to remember once in a while.

Comments

Post a Comment